This is a transcription of a presentation at GDC 2021 by Justin Keenan of ZA/UM, concerning dialogue conventions in role-playing games and its praxis in Disco Elysium.

As noted by GDC, Disco Elysium may be one of the best and most critically acclaimed RPGs of this century - in my opinion, possibly even this millennium. I highly recommend you buy it and play it.

(spoilers ahead)

Meaningless Choices and Impractical Advice

Hi my name’s Justin Keenan. I’m a writer for ZA/UM and today I’m gonna talk a little bit about branching dialogue design in Disco Elysium.

When Disco came out, we got a lot of praise for the quality of our writing and our approach to branching dialogue more generally, so I thought this would be a good opportunity to speak a little bit about some of our design principles as a studio, as well as where the state of branching narrative and dialogue design are, as an art form.

So at a fundamental level, the main thing that distinguishes branching dialogue in Disco Elysium from many other CRPG’s that you may have played, is that we think of its function as primarily aesthetic or textural, as opposed to instrumental - by that I mean that we really push to make every dialogue as particular and strange and true to the characters in the scene as we possibly could. You might think that this is how all RPG’s do it, but it’s really not, and I’m going to explain what I mean.

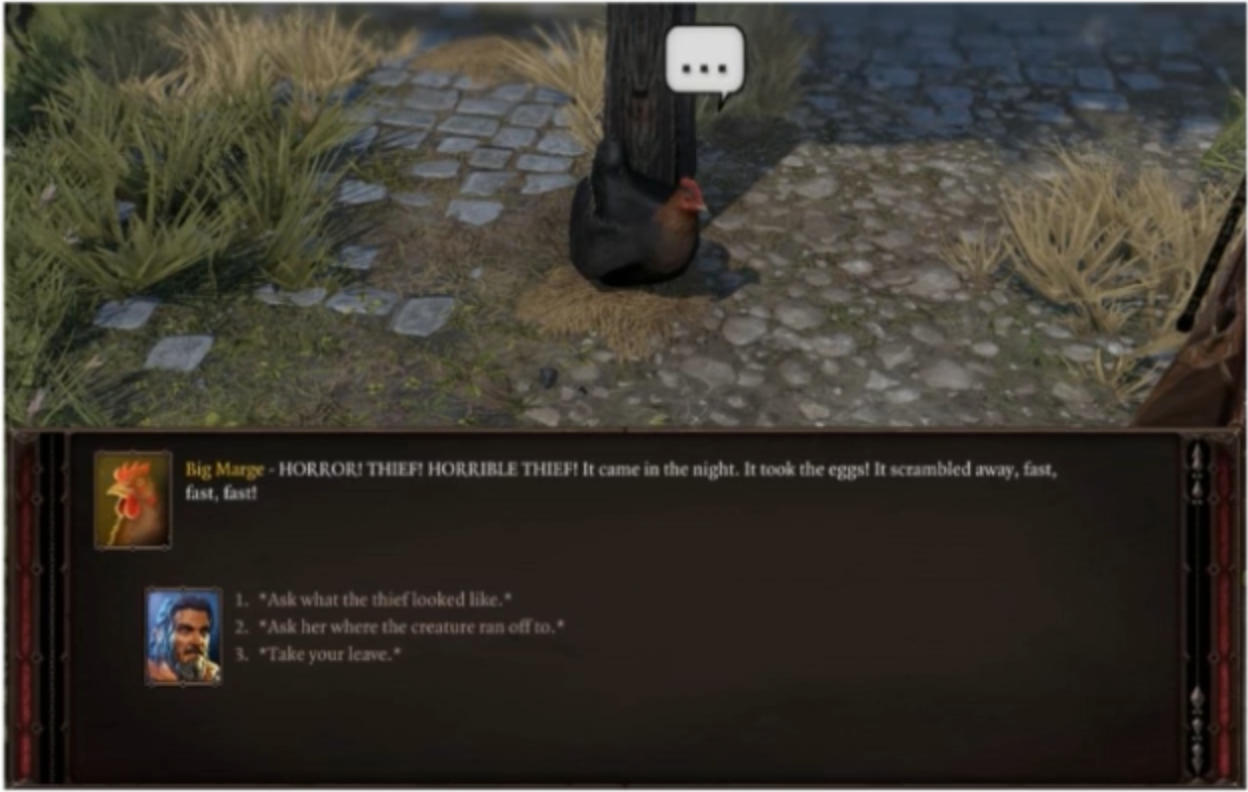

If you’ve played even a handful of RPG’s, you’ve probably developed a sixth sense for what a character’s narrative function is going to be the moment that you meet them. This is why any time you meet somebody in a moment of crisis, or they’re calling out to you for help, or even if they just seem engaged in some sort of frantic activity, you know right away as a player that if you ask this person “what are you up to, what’s going on?” that eventually they’re going to give you some kind of task to perform for some kind of reward.

Now maybe you can also talk to this person about their life, or their work, or their innermost political or spiritual opinions or whatever, but as player you know none of this stuff matters as much as the fact that their prized chicken or amulet, or daughter or whatever has gone missing and that if you bring it back you’ll get some experience points and gold and enchanted family shield or shotgun or something like that. No matter the game, the form of these interactions, which is to say their narrative function, is the same - which is kind of the point.

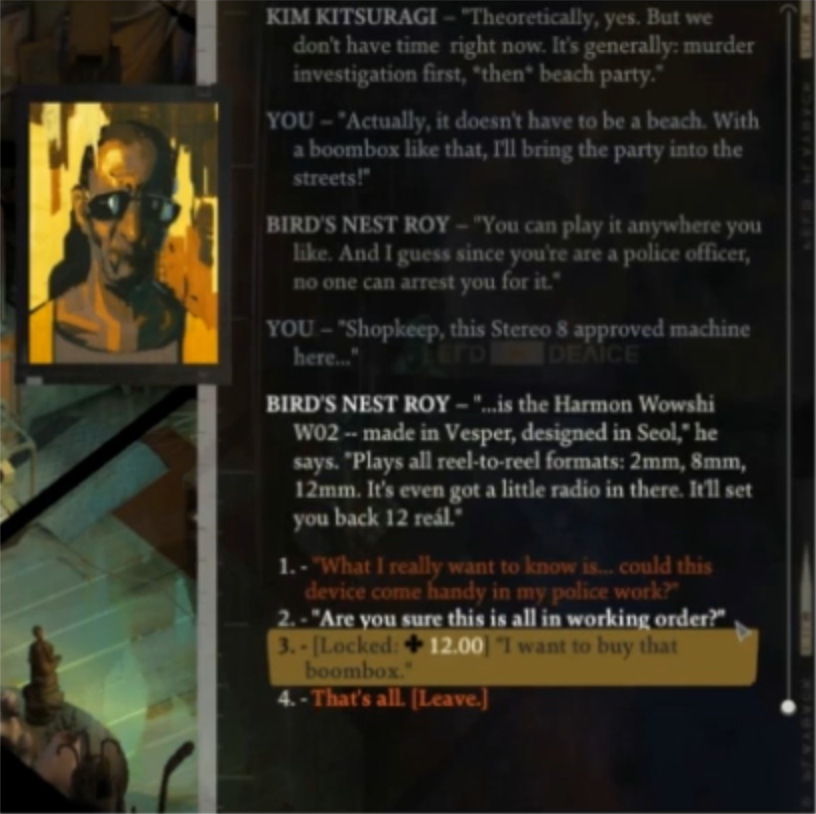

So in Disco, we tried to get as far away from this approach as possible with our dialogue and narrative design. Of course, these dialogues still serve narrative functions; we still have shopkeepers and quest givers and area bosses after a fashion, but our main concern when we write and design them is to make each one as interesting and particular as we possibly can. This is why when you talk to Roy the pawnbroker, who is one of the shopkeepers in the game, you don’t just talk to him about things that you might be buying or selling or general information about the area - you can really go deep on his personal history which, you know, in his youth he spent some time cleaning up a nuclear waste disaster. He also has some very exotic opinions about music and psychedelics, none of which have any obvious relationship to the main plot of the game, though it does serve to make our pawnbroker Roy feel like a real human being with weight and substance in the world, and then of course, a few of those things may end up having narrative significance, though as a player, you won’t realize it at the time - which, again, is the point.

So what are some of the particular features of our approach to branching dialogue? I put together four here that I think are important and I’m going to speak to each of their qualities and some challenges that go with them.

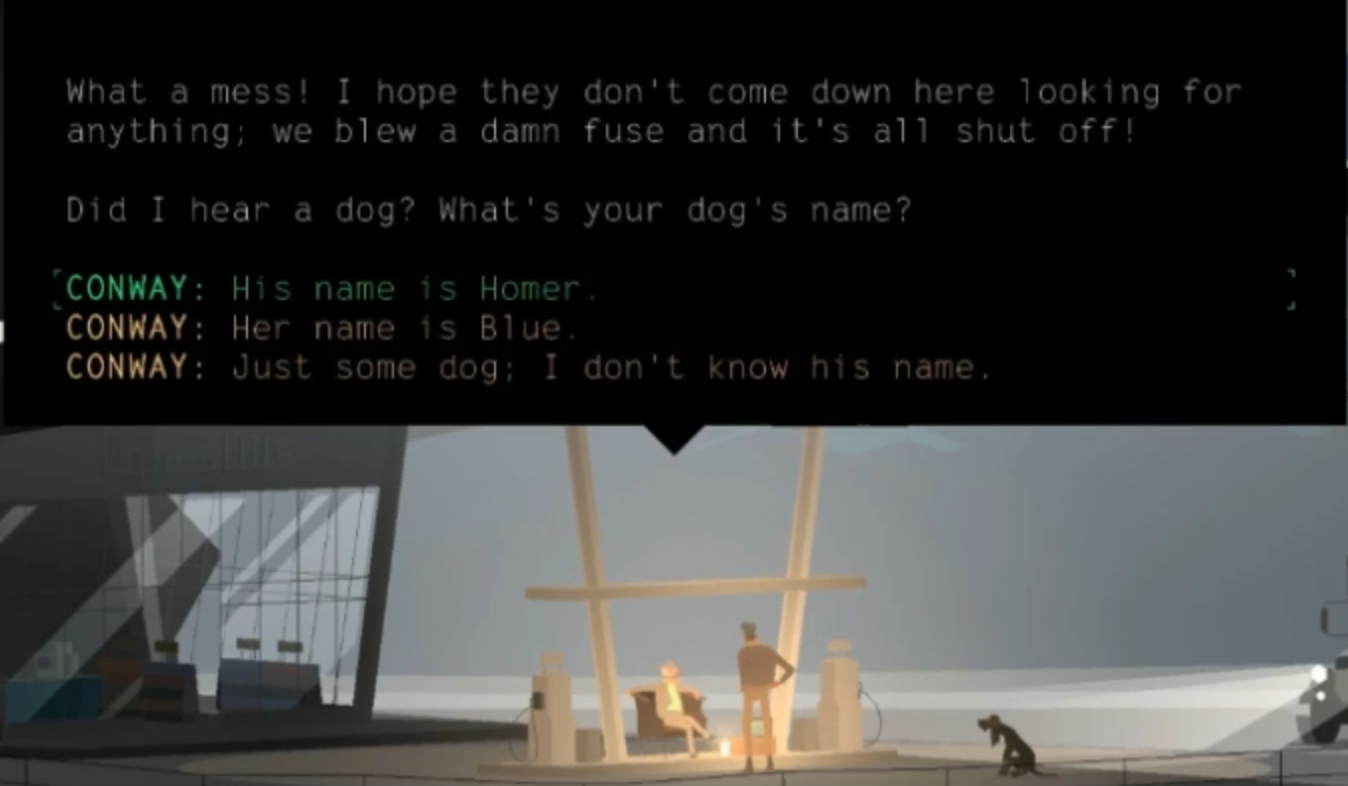

I want to start with something that we call micro-reactivity, which is when the game seems to remember and respond to even your most trivial decisions as a player.

This is a fairly straightforward example from Kentucky Route Zero which is one of my favorite games. It’s actually, I believe, the first decision you get to make in the game, and as you can see, you’re deciding what the name and gender of the dog that accompanies you is gonna be.

So obviously whichever option you choose, every time this dog comes up in conversation throughout the game and the game’s gonna remember what you named the dog and what its pronouns are et cetera.

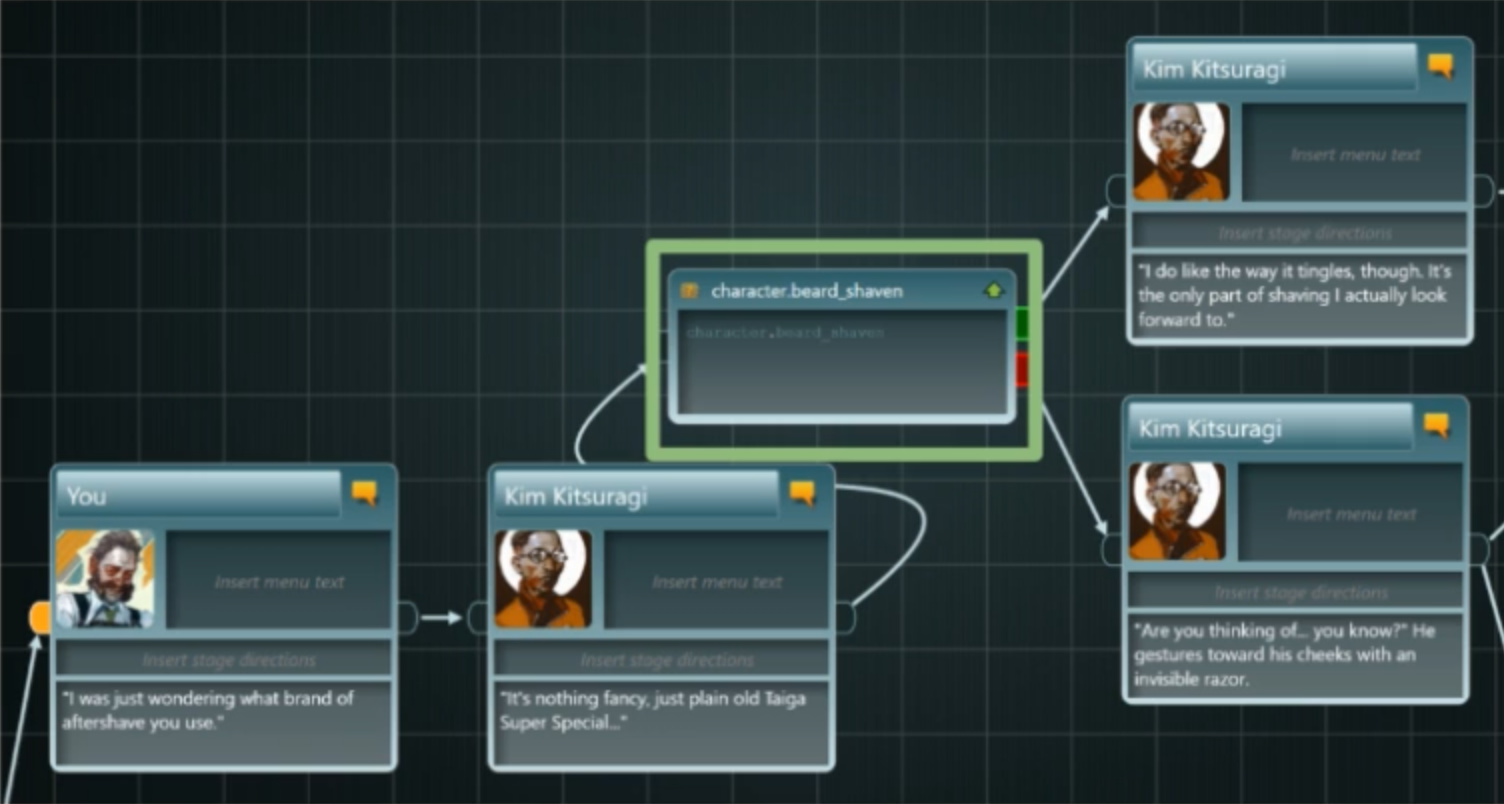

This is a similar example from Disco: at a certain point in the game, you may get the option to shave off the horrendous mutton chops your character starts with, and if you do, the game will flip a little boolean switch which lets us know that whenever your beard gets mentioned, the game will check to see whether you still have it and then give you a different dialogue option depending.

So in this example here, you can see that your partner Kim - you’ve been talking to him about his brand of aftershave - and his response to you will vary depending on whether you have recently shaved yourself or not.

One extremely sensible piece of advice that you sometimes hear from narrative designers is that, you want to avoid these things that are called ripples, which are instances where players’ decisions echo or ripple outward, to affect many additional choices sometimes in ways that the game designers can’t predict or account for.

In open world games, these ripples are especially dangerous because they can create either game-breaking bugs or sort of, like, ludicrous and embarrassing logical holes. For instance, a character that you killed is still referred to as being alive later on in the game. But the thing that we’ve been calling micro-reactivity is essentially a process for generating narrative ripples on an almost industrial scale. There are probably thousands of these micro-reactive moments throughout the game and the problem for us as designers is that once you, you know, commit to the principle of micro-reactivity there is like, no end to it. Like even to this day, when I played Disco Elysium, I still run into moments where I think “Ah, we should have had some reactivity here for this-or-that choice that the player could make”, but we didn’t think of it, or we didn’t get to it in time.

And the other thing is that, once you have something like micro-reactivity in your game, players will definitely notice it and they will also notice, of course, when it’s not there.

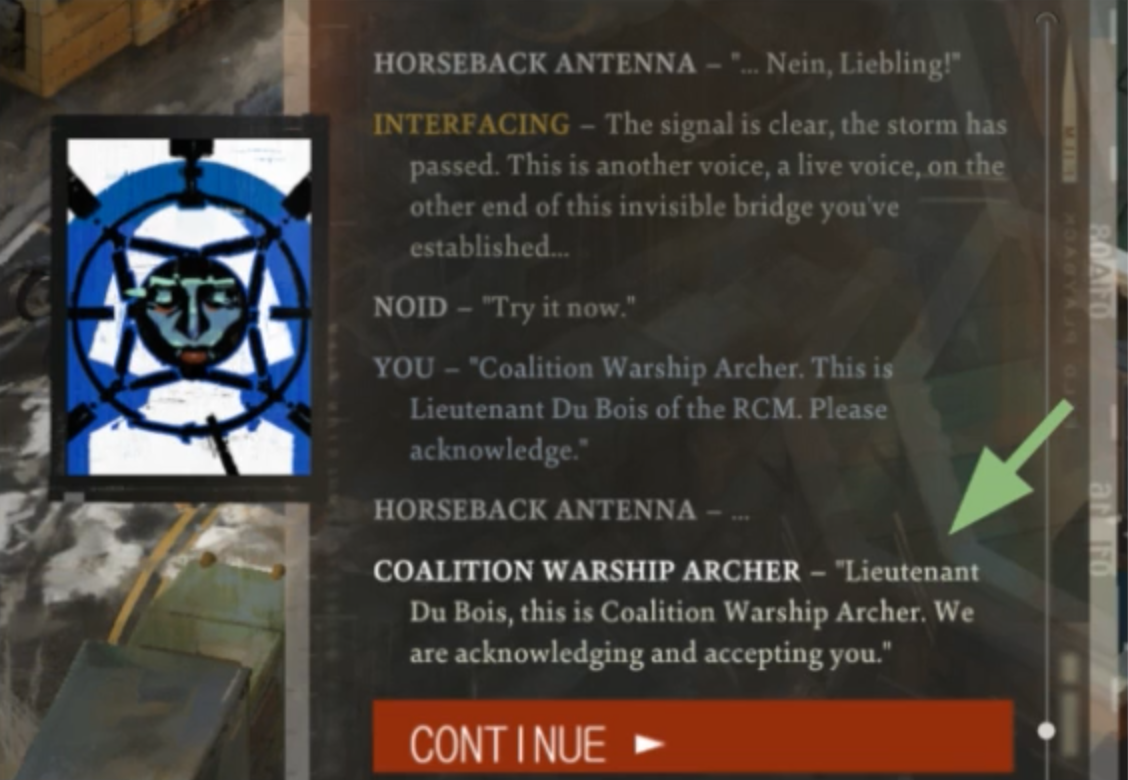

Now I want to share with you a truly brain-damaged example of micro-reactivity that also gets at some of the hazards of this. During one of the new quests that we added in the final cut, you can find yourself talking with the radio operator on a coalition warship, and as a writer on that quest, I thought it would be cool for the player to be able to choose a call sign for their character, and naturally I wanted those call signs to reflect the various names that your character can choose to adopt over the course of the game. So I drafted this dialogue and I wrote it out and I included placeholders and so on, and then eventually I came back to write all the different variations for these calls signs and so on, and then implement the programming that would make them work, and at that point, I realized I had gotten myself into a tremendous mess because there are four call sign variations for every instance where a call sign occurs, and sixty-two instances where either you or the radio operator uses one of these call signs which means that this element of micro-reactivity created a total of four-hundred-and-twenty-eight dialogue cards that had to be written, programmed, translated into a half a dozen or so languages, voiced by our voice actors, and then QA’d. And so you might say “Justin, this is an obviously asinine idea and you shouldn’t have gone with it because it was very clearly going to be a lot of work”, and that’s true, but the thing is, even though it was my idea, the decision, in a way, had been made much earlier in the design process. By which I mean, the moment we decided to give the player the latitude to select different names for themselves and run with that joke or bit or whatever you want to call it, it basically forced me to account for it in the scene, because I knew that players would reasonably expect to be able to use those names when it came time to give this warship operator their call sign.

At the same time, when micro-reactivity works, it is probably the closest that an RPG can come to replicating the tabletop experience of having a very good dungeon master sitting across from you, listening to and responding to your most idiosyncratic choices as a player, which is why the players who play the game really tend to like these moments.

So now I want to talk about something that I call a rhetorical approach to branching dialogue, which is a way of saying that we treat the branching dialogue structures in our game as aesthetic objects that can evoke certain emotional or intellectual responses from players. This concept is probably familiar to anyone out there who is a writer or novelist, because you know that this is also true of individual sentences, like different sentence structures have different rhetorical and aesthetic properties, like short staccato direct sentences create a different feeling in the reader than a long and winding hypotactic sentence. And it’s the same with these dialogue structures. And so here I think is a good place to mention that, at ZA/UM, there’s no distinction between writers and narrative designers like there is at some other studios, and so for the most part, the person who designs a character in a scene also writes the characters and dialogue in that scene, which I think is the only way for this kind of unified rhetorical approach to really make sense. And for my part, this is, I think, where Disco Elysium most pushes forward the art of branching dialogue design, because it’s not something that I think has really been explored before.

So let’s look at a couple of examples. This is one of my favorite scenes from the game. It’s part of your first conversation with Kim, who is your partner in the game, and it comes right after you’ve stumbled down from your hostel room, where you had blacked out and lost all memory of yourself and reality. And the thing that your partner Kim wants to know in this moment is whether you have removed the dead body from the tree.

So from a certain vantage point, this is a completely pointless moment full of false choices, which are generally considered no-no in branching dialogue design, because they irritate the player and so on, but in this case it’s also one the of the most memorable scenes in the game, because as a player, you immediately get what’s happening.

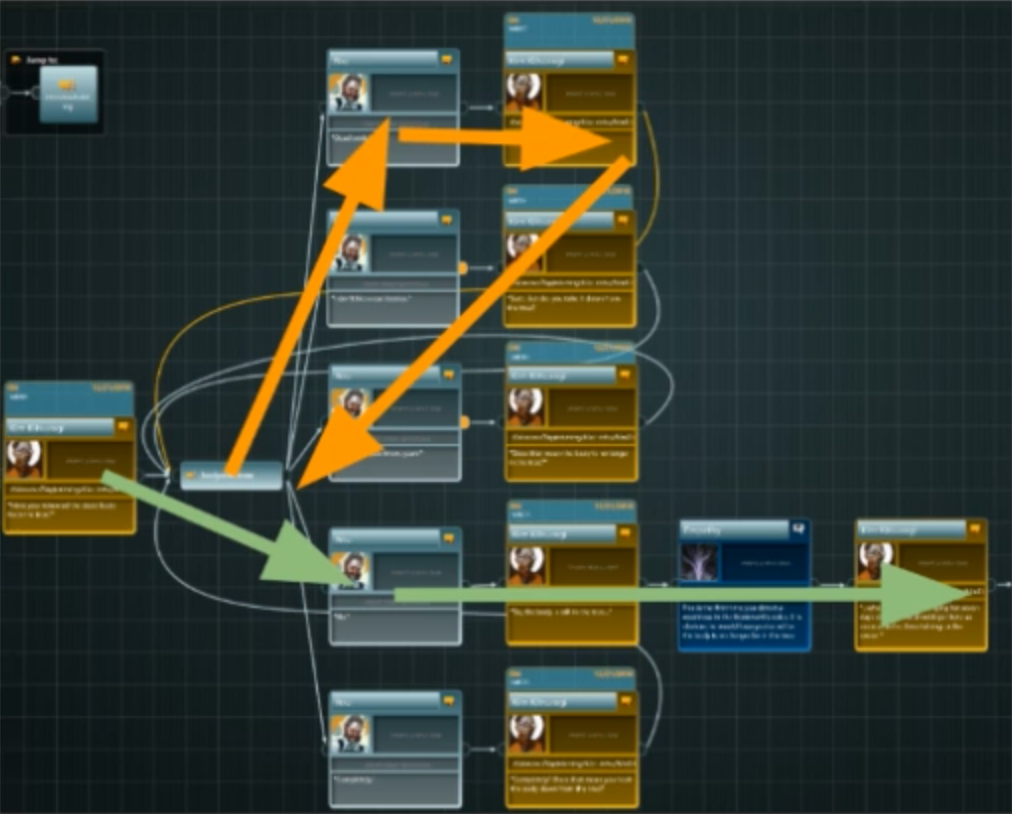

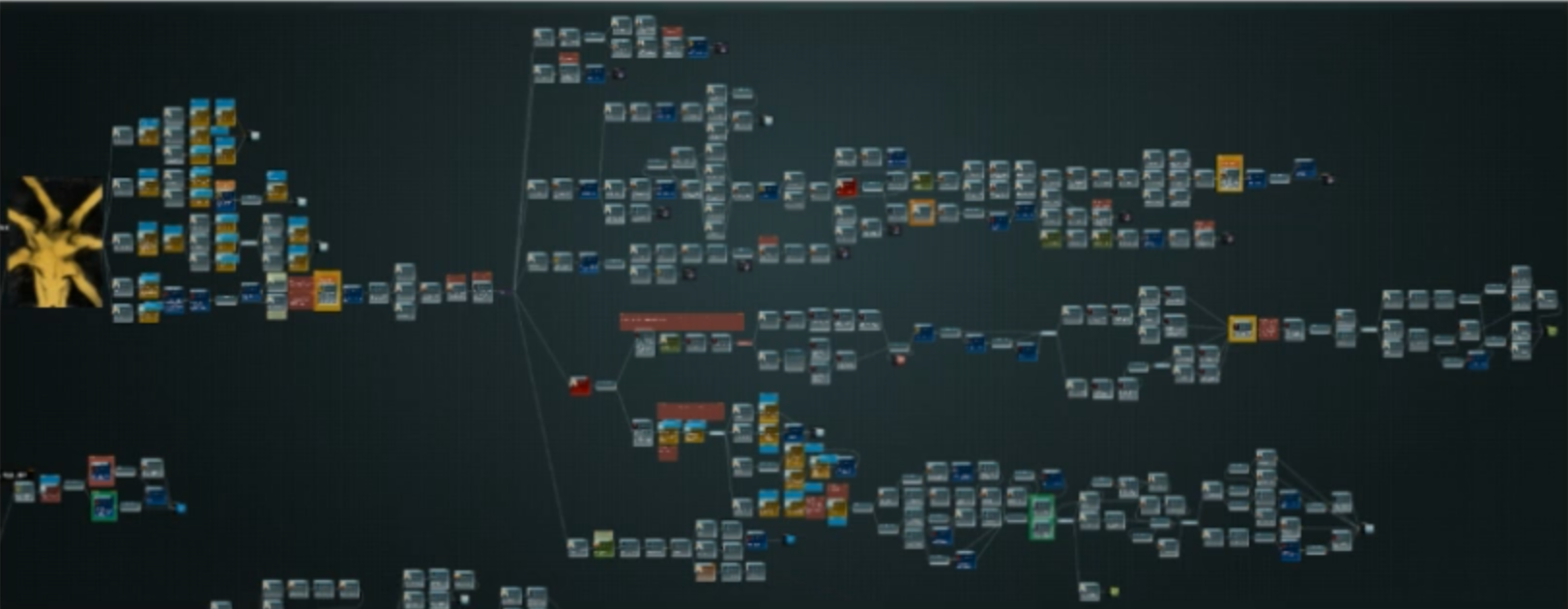

So, here you can see how this moment looks in our dialogue management system, and visually you can see that the only way forward through the dialogue is by admitting that - no, obviously you have not taken the body out of the tree, and every other option just kicks you back to this little hub here. Not only that, there are no secret booleans or counters that are keeping track of your decisions here.

So it’s truly, like, a pointless moment from a mechanical standpoint, and yet, I’ve watched dozens of people play through the scene, and nearly every time this magical thing happens which is, the player reaches this moment, they see perfectly well that they have to say “no” to advance the scene, they chuckle because they get the joke, and then they proceed to click some or even all of the other dialogue options, because it’s fun to do that, and because they want to see how awkward and excruciating they can make this scene for their character. And this particular dialogue structure which we happen to call a whirl, is well-suited to creating that kind of moment.

So now I want to look at a more complicated example, which comes from a conversation later in the game with the character Cindy. Here you see, what looks like two separate branches, but in fact is really just one. We call this structure, by the way, a river, because no matter how the player clicks through the various options they still flow linearly and inevitably toward the same place.

So you might be wondering what that other branch up at the top is, and it is something that we call a detour or hold-up, which is essentially what it sounds like - a little kind of loop that eventually leads you back to the main branch, and you may notice that in order to reach this detour you have to take a very particular path which is up through this top branch and down and then you will hit this esprit de corps passive check, which requires you to have a very, very high esprit de corps skill - it’s quite unlikely to have this point of the game - if you do that then you trigger this detour moment, which is a kind of flash sideways to a conversation between two of your squad mates back at the station. It’s a sort of special secret moment for players who happen on this very particular path.

Now if you’re looking for a reason not to do these sorts of rhetorical flourishes, here is an extremely good one: the ROI from these moments from the production standpoint is horrifically, unbelievably bad. A very practical piece of advice that we received from some friends at other studios is that you should design toward the median player. In other words, as a studio, as writers, as designers, you shouldn’t waste time on material that the vast majority of players won’t see. Here in this moment, I would bet that less than one percent of players are likely to encounter this detour that we put together, and so that’s an additional fifteen or so cards that all have to be written, edited, translated, QA’d, voiced, for seemingly little purpose, but the thing is, there are several hundred of these moments throughout the game, so the ninety-nine percent of players who miss this moment are very likely to encounter several others, each of which will feel special and and particular to their playthroughs. And so, not only does this create a desire on the part of the players to play the game again and see what other secret special moments they can uncover, it creates this extremely important illusion that the game itself - even though it has a finite but very large number of words - that it is in fact a kind of infinite storehouse of these sorts of secrets that are just waiting for a diligent player to uncover.

So next up is a pretty straightforward idea, which we call minimizing gamification, which we’ve kind of already talked about in a way. It’s this idea that as a studio we’re always trying to get players to quit treating our dialogues like means to some narrative-mechanical end and to rather engage with them the way they would an actual conversation with a real human being.

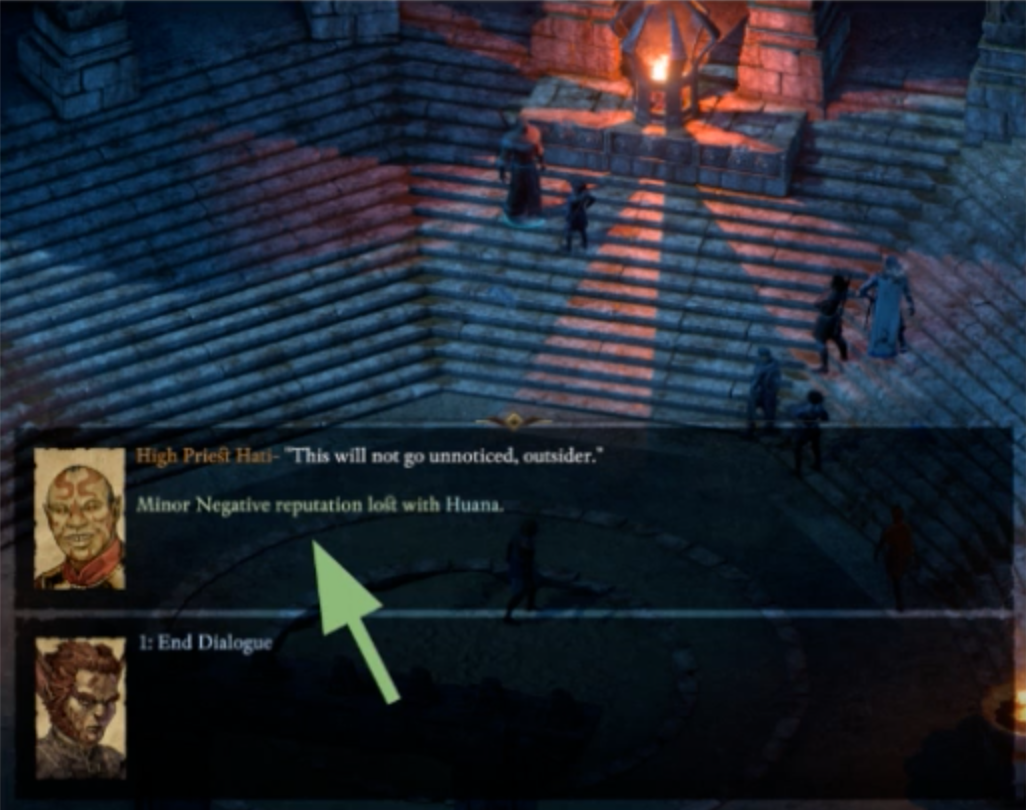

To that end, we try to downplay elements that remind players that they’re inside a role-playing game. This is a good example of one of those elements, it’s from Pillars of Eternity 2, and you can see here that my character has just said something very offensive to this priest, and that the game has very helpfully informed me that this is going to minorly damage my relationship with the priests faction going forward.

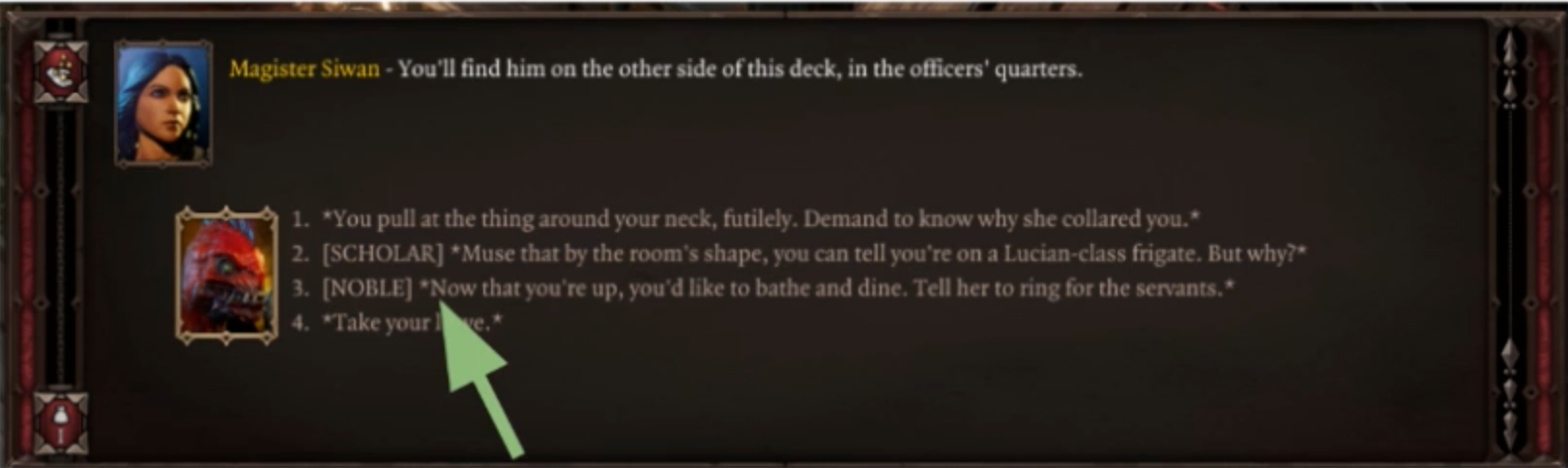

Here’s another example from Divinity: Original Sin 2. You can see that my red lizardman here has certain options that are labeled [NOBLE] and [SCHOLAR] because my character happens to have those particular background traits. These things are sometimes called ‘agency indicators’ by the way, because they indicate that your choices have agency in the world.

The thing is, this is a very tricky balance to strike, because as game designers, we naturally want players to know how much work we’ve put into catering to their decisions and whims and so on, but I think in moments like this we also risk, kind of, putting our thumbs on the scale too much by not-so subtly encouraging players to pick these cool, tailored, special options - while also kind of implying that the other options are somehow lame or generic, which is another form of false choice, by the way.

Here’s an example, from Disco, of a moment that’s more-or-less equivalent to that scene from Divinity, only you wouldn’t necessarily know it at first glance - which again, part of the point. Here we’re back in Roy the pawnbroker’s shop, and here you have a chance to offer an opinion about the goods in his shop, each of which is tied to one of our game’s political ideologies, because in Disco, we love to give you chances to express your political opinions.

And, of course, an attentive player will probably be able to tell which of these options corresponds to which ideology, but the point is we’re not signalling to the player: “hey, this is a moment of political import”, instead we want to encourage them to engage with the system as naturally as they would any other dialogue option.

Of course, it doesn’t mean that we don’t have any gamified elements. We do use some standard bracket tags like “leave” for an option that ends a conversation, or “proceed” when we want to be absolutely clear that a given dialogue advances that branch further. I should say, we didn’t always have these elements, but at some point in the development we realized that we needed to add them, because some players were getting a little too lost in our dialogues, and, you know, if you if you don’t have these obvious tags, it places an additional burden on the writing to very clearly communicate, like, what is still happening at a mechanical level.

But when it works, again, players kind of forget that they’re in a game, and that’s when these sort of magical things start happening inside their brains.

So lastly I want to spend a little bit talking about something that we’ve taken to calling radical asymmetry, which is really more of a design philosophy than a guideline for reading individual dialogue, but I think you’ll see how it ties together certain themes that we’ve been talking about.

Put simply, radical asymmetry is the idea that players who approach the game differently should experience it dramatically differently. This kind of comes as a reaction against certain old habits in RPG design.

First, if you played a lot of CRPG’s, like Morrowind for instance, you’ve probably encountered some version of this phenomenon, where, you know, for every major class there is a corresponding guild or stronghold in a major city or whatever. This is also true in Baldur’s Gate, and so on. The idea is that the game is going to provide you with something special no matter what class you’ve chosen.

The thing is, whichever class you pick, whichever stronghold, or guild, or faction, or whatever that you join - narratively, the role they are going to fill will be symmetrical, which is another way of saying that they’re kind of interchangeable.

Josh Sawyer, the director on Fallout New Vegas, has an excellent GDC talk from some years ago about choice architecture and he argues in that talk that it’s important to validate any expression you allow your player to make. So, for example, if you allow your player to play as a sociopathic conman and murderer, that player should still have as meaningful a narrative experience as the ninety-five plus percent of players who are going to play a paladin and paragon of virtue, or whatever.

The thing is, that doesn’t mean that you have to validate all of them in exactly the same way because - this is a kind of a political stance of ours that we take very seriously - no human society, and reality, in general, validates all beliefs or kinds of people equally, and so it was very important to us that the world of our game reflect that.

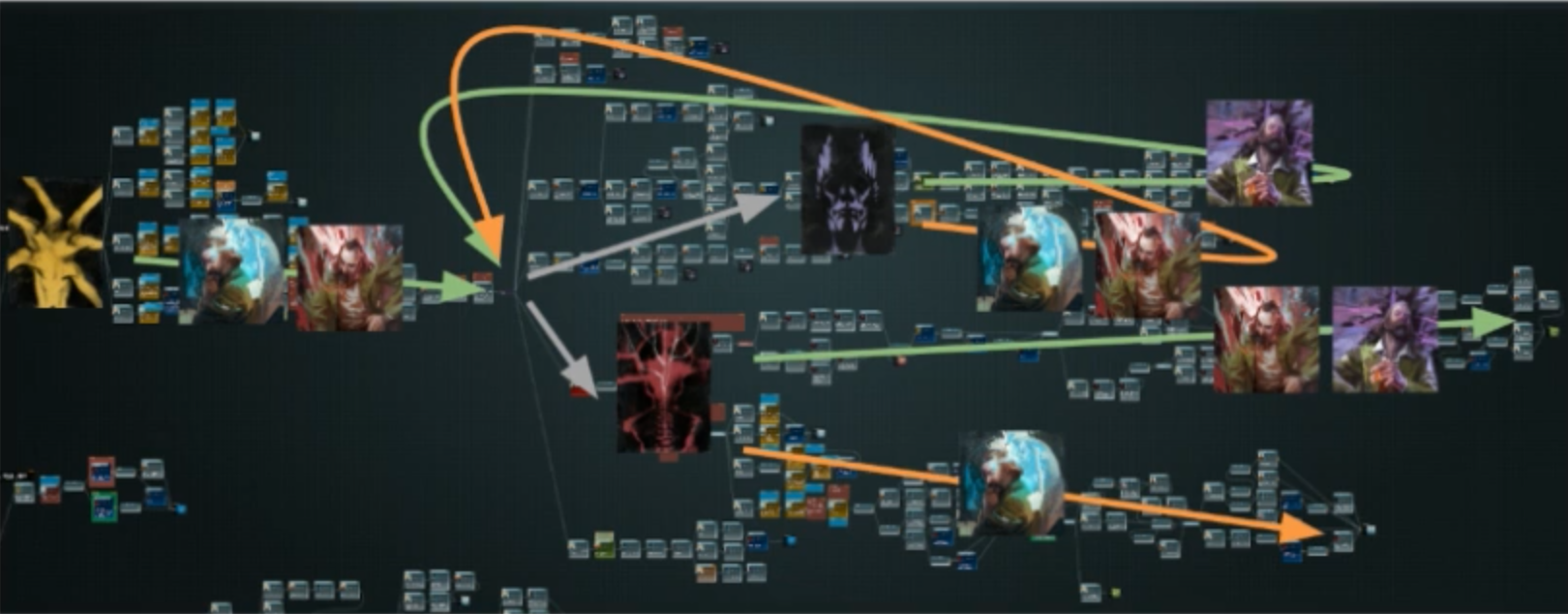

So, let me give you a somewhat involved example. We’ll start with our player archetypes, which are the most basic way the players start to distinguish characters from the start of the game. We’ve got three archetypes: the thinker, the sensitive, and the physical, which we sometimes shorthand as Sherlock Holmes, Dale Cooper from Twin Peaks, and Vic Mackey from The Shield. They all start with different skill point allocations, so far what you would expect, but now let’s look at how these different archetypes shape the players’ experience of one scene that, I think, perfectly captures this value of asymmetric design.

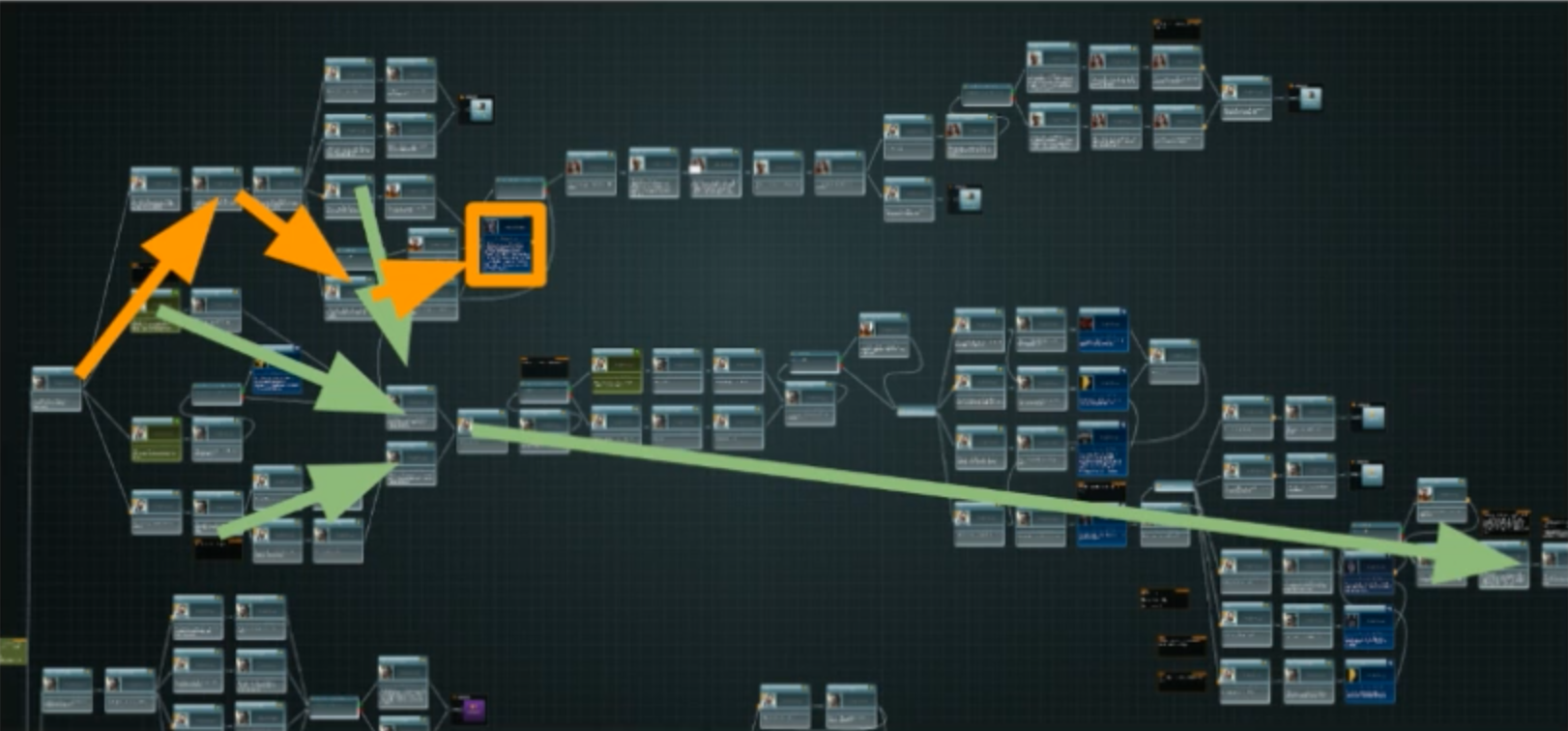

So we’re gonna look at the church dance scene, which some of you might be familiar with. If you’re not, it’s the combination of one of the larger, kind of, side-quests in the game and it gives you the chance to break out into dance in the middle of the spooky old church that you’ve just turned into a nightclub and potentially a speed lab as well.

So here’s what the scene looks like in our dialogue management system. To start the scene, the player first has to pass a savoir faire check, which is basically a measure of their physical dexterity and sense of panache or cool or what have you, and from there, the major points of interest include a couple of red checks, which are these non-repeatable checks that have very high stakes for the player.

So, here you can see the first one is an authority check which is kind of notorious in the game, because if you succeed in this check you convince your partner Kim to dance with you and it’s a high point in the game for a lot of players - they make memes about it, it’s all great fun.

The problem is, if you fail that check, you call your partner, Kim, a slur and he storms out of the church. This is a devastating moment for many players, which is why they tend to immediately reload and then replay the scene, which I have mixed feelings about, but whatever.

The point is it’s a kind of classic high risk, high reward moment from the players’ point of view. Now the thing is, there’s this other red check, which is a shivers check which is a very spooky moment for the player because up until this point the shivers skill has typically been reserved for offering long, lyrical descriptions of the weather and so on, and so players will, kind of, justifiably, like, wonder what is really going on here.

If you fail this check, your character will pass out from dehydration - turns out you’ve been dancing harder than you’re really able to maintain, and narratively, nothing bad happens. The scene still ends on a very satisfying note, especially for what is fundamentally, like, optional side content. If you pass though, your player character will experience a truly transcendent, possibly supernatural, vision in which the voice of the spirit of the city speaks to you and reveals that your character has an important role to play in events that have yet to transpire. So, for the player who passes this check, it completely transforms the meaning and significance of the scene and in fact the whole quest leading up to it goes from being a seemingly side venture into one of the major narrative climaxes and threads of the game.

So in other words, it doesn’t just end the scene, it recontentexualizes a major part of the narrative in a very new and exciting way and there are, I should say, a few of these types of moments throughout the game.

So I hope it’s clear by now that designing this kind of asymmetry into a game takes a ton of careful design work, and it’s often very brittle work that sometimes is in tension with our impulse to let writers kind of design as they write, which goes back to that idea of the rhetorical approach to branching dialogue.

A theme to this talk, which I hope is also apparent now, is that there aren’t very many shortcuts around all the writing that this kind of design principle requires. We don’t have many programmatically generated or clever scripting tools to help us write all this material. It’s all carefully designed work, and then just, like, an ungodly amount of writing which is why for a game that’s only twenty-five hours or so, there’s still almost a million or, now, more than a million words that go into the script.

To illustrate this point further, I want to look at how each of those archetypes we looked at earlier are likely to pass through the scene. To be clear, I’m simplifying quite a bit here, but you’re gonna get the idea.

We have the thinker and the physical archetypes, who both happened to be fairly dexterous which makes passing that savoir faire dance check pretty easy for both of them. Unfortunately, both of these characters are quite bad at social interactions - they have very low psyche skills which makes them both very likely to offend Kim and drive him out of the church. So now, assuming that these players haven’t saved and reloaded the game, they’re now going to come to that potentially transcendent shivers check, and here they’ll kind of diverge: the person playing the physical archetype, who has much higher physique skill (which shivers falls under), is way, way more likely to get that transcendent moment than the hopelessly nerdy thinker archetype who is very likely to over-exert himself and pass out from dehydration. This leaves the third archetype, the sensitive Dale Cooper-type guy, who is by design, somewhat maladroit, so he’s going to have a very hard time passing that initial savoir faire check, but if he does, he is more likely, because he is much better with people, to convince Kim to dance with him, and then because he is also more attuned to the, sort of, spiritual dimension of the world, he’s also quite likely to pass that shivers check.

So you can start to see how the arc of the scene plays out very differently depending on the archetype you’ve chosen. Like, if you’re a thinker, it can start at a high point and then follow two successive disasters, whereas the sensitive may have a very hard time starting the scene, but then experiences, like, this one-two punch of escalating, you know, reaffirming climactic moments.

And that also gets at some of the potential downfalls of this approach, which is that whoever is playing the thinker is much more likely to feel like they never had a good shot at getting the good outcomes of this scene. In other words, they may feel like the game isn’t properly validating their archetype, and to a certain extent, that may be true, but that’s because in real life, overly cerebral types also happen to be very bad at dancing and talking to people generally - I speak from experience here. That said, the thinker also has several cool game-defining/game-redefining moments that they are much more likely to uncover than either of the other archetypes, which again gets back to both the beauty of radical asymmetry, but also a real challenge for it.

So this brings me to another theme of this talk which is that we put a lot of emphasis on creating meaningful replay opportunities for players, even though the broad contours of the story itself are gonna stay relatively consistent from game to game. And part of why we’re able to do that is that, this magical thing happens when players become deeply invested in their character’s experience, and this is sort of where all these different features of our design process, kind of, come together, which is to say, when they cease to think of a game as just a collection of mechanical systems, and start treating it like a story that they happen to be guiding with their actions. They begin to experience conversations and events they’ve seen before as though those moments are new again, because the conversations and events are recontextualized or transformed by the new perspective that their new playthrough creates.

So before I wrap up, I want to briefly touch on a couple of questions that I and some of the other writers at ZA/UM are still thinking about.

First, and for all intents and purposes, dialogue is the gameplay loop in Disco Elysium. There are a couple of other systems that the player will engage with, but compared to other RPG’s these systems are relatively primitive, and I’m very curious to see what happens if you attempt to combine our, sort of, very sophisticated dialogue systems with other more complex, say, combat or strategy mechanics. Would that lead to something transcendently good? Or will it just be too much of a mess for players to follow? I don’t know the answer to that.

The last point goes back to that rhetorical approach that I described earlier. In short, I think even with Disco, we’ve only barely begun to explore what sort of emotional and intellectual experiences we can create for players with these branching dialogue structures. One of my preoccupations now is starting to develop a more formal theory of how players engage with branching dialogue, because like I said I think this is the main way that we’ll continue to push this art form forward. That’s all I’ve got for you. Thank you so much for your time.